Cognitive Load and 9 Implications for Increased Productivity

Cognitive load is the amount and type of information your brain can hold and process at one time.

Obviously, there’s a limit to your cognitive load.

You can’t do too many things at once, and you certainly can’t do a lot of things well at one time.

Cognitive load theory, then, states that if we want our brain to function at peak performance, we must be intentional in the types of mental tasks we take on.

This article isn’t for cognitive theorists or neurologists, nor was it written by one. But for multitasking information workers, understanding and applying cognitive load theory is of utmost importance.

Why?

- By understanding cognitive load, you will better utilize your limited mental energy, contributing to increased productivity.

- When you put cognitive load theory into practice, you will be able to perform at a higher level for a longer period without experiencing unwanted mental fog or burnout.

- Cognitive load theory has enormous implications not just for getting more done in your day, but getting more done better.

Busy professionals like us need to know about cognitive load theory in order to more strategically use our time, protect our most valuable asset (our mind), and accomplish what truly needs to be accomplished each day.

By tracing out the implications of this powerful theory, you’ll be able to do just that.

First, let’s go through some of the science, because it will improve your ability to absorb the productivity implications at the end of the article.

What Is Cognitive Load Theory?

Cognitive load theory asserts that because working memory is limited, then we should take in limited amounts of information and in ways that make the least demand on our working memory.

What is Cognitive Load?

Cognitive load is the amount and type of information that your brain can take on and store in its memory at any given time.

There are three broad types of memories, each of which contributes to your cognitive load

Sensory memory – short term memory taken in by the senses

Your sensory memory takes in information from your body’s senses — primarily visual (iconic), aural (echoic), and tactile (haptic).

Your brain hangs on to these memories for anywhere from half a second to ten seconds, depending on the input method, intensity, etc.

After a few seconds, your brain retains only impressions of the sensory information in the absence of the stimuli.

Your brain will hang on to that sensory memory, placing it in working memory if it deems the information important.

You signal that the memory is important by giving it your attention.

The coffee cup to the right of my computer is off white and has leaf patterns. I think I have about a half cup of coffee left. And I think it’s lukewarm. I can smell it. Two of my fingers can fit into the handle at once.

Actual footage of the coffee cup in question.

All of that sensory input is part of the cognitive load.

And that’s the first stage of memory.

It’s always on. And it takes an enormous amount of mental energy. You’re bombarded with sensory input on a constant and ongoing basis.

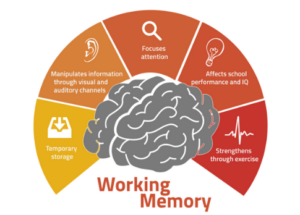

Working memory – determining whether to focus or forget the sensory memory

As your brain processes sensory input, it may move it into its working memory.

Your working memory must continually decide whether to keep the information — give it attention — or discard the memory.

Forget? Or Retain? That’s the question that your working memory has to decide.

Your working memory is your brain’s organizational center.

It’s going to decide what memories become schemas.

And that’s where long term memory comes into play.

Long-term memory – creating schemas that define how and when you use those long term memories

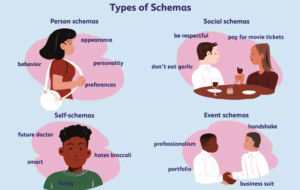

Your long-term memory creates schemas.

Schemas are basically knowledge structures.

Your brain has a schema for cat, which it has formulated by all the relevant sensory input it has received.

It’s safe to say that your brain has millions of schemas, each of them with a particular nuance, features, overlap, and the fleeting or persisting sensory recall.

Your brain also has behavioral schemas — ways of acting, moving, and responding. For example, if you can ride a bicycle, then your brain has developed a behavioral schema that involves sensing your balance, using certain muscles, etc., in order to stay on the bicycle in a safe and motion-oriented way.

Eventually, these schemas become automated, reducing their impact upon cognitive load, and giving your working memory more flexibility.

An Example of the Cognitive Load Theory in Action

Let’s dive right into an example, and that will help you understand the science behind cognitive load theory a little bit better.

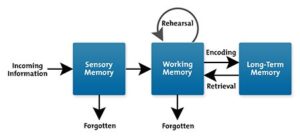

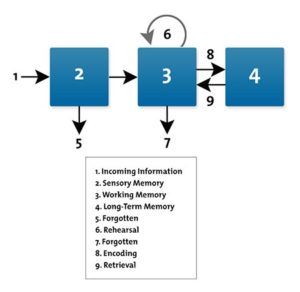

I’m going to show you two diagrams.

The information in each diagram is the same.

The presentation of the information, however, has a different effect on cognitive load.

(Don’t worry about the content of the diagram even though it relates to cognition. Just focus on the layout.)

Here’s the first one.

In case you’re curious, that’s the information processing model.

Interpreting the diagram is really hard!

You have to look at each number with its corresponding arrow, shift your attention from that visual cue to what that number indicates, store that bit of information in your short-term memory, then move on to the sequential number and its attendant representation, hold that in your memory, and move on until you reach number nine, at which point you’ve forgotten everything.

If I tried to learn information processing based on that diagram, my mind would implode and I would probably be more likely to yell at my kids and not feed my dog. (I don’t have a dog, but that’s not the point.)

Seriously, that’s the kind of fallout consequences that cognitive overload can have!

This diagram is almost useless.

Why? Because it violates everything that the cognitive load theory tells us that our brain can handle.

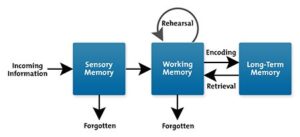

Let’s take a look at the same diagram, presented in a different way.

Same info, but new layout.

Gone is the number key. Instead, the flow chart is equipped with built-in descriptors.

You can spend far less time studying this diagram and retain way more of the information that is presented in it.

Why? Because of the reduced cognitive load provided by the layout of the chart.

Your sensory memory doesn’t need to retain the visual (iconic) input for very long. Within a split second, it’s reading the label and tracking its position, storing it in the working memory long enough to retain all the pieces and thereby understand the diagram.

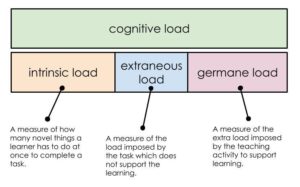

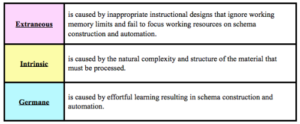

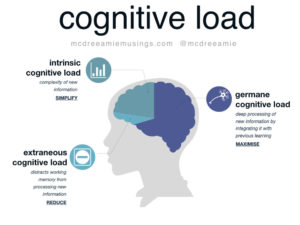

Three Types of Cognitive Load

There are three main types of cognitive load — intrinsic, extraneous, and germane.

Intrinsic Cognitive Load – How Difficult the Problem Is

Intrinsic cognitive load refers to how difficult a task is.

For most people, 2+2 has low intrinsic cognitive load.

It draws on few schemas and, for most of us, the answer to that problem is automated.

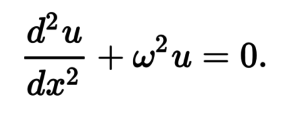

But if your problem were to solve a nonlinear differential equation, the intrinsic cognitive load increases. That problem is more difficult.

Want an example?

Here is a homogeneous second-order linear constant coefficient ordinary differential equation describing the harmonic oscillator, a system that, when displaced from its equilibrium position, experiences a restoring force F proportional to the displacement x, where k is a positive constant.

Did you catch that?

Probably not.

Why not? Because the intrinsic cognitive load level is quite high, requiring multiple schemas.

Unless your brain already has those schemas and can access them, you won’t be able to solve the problem.

Extraneous Cognitive Load – The Way Information Is Presented

Extraneous cognitive load refers to the manner of presenting information.

In that example above — the diagram example — you saw this in action.

One diagram was cumbersome and difficult to read.

The other diagram was a lot easier.

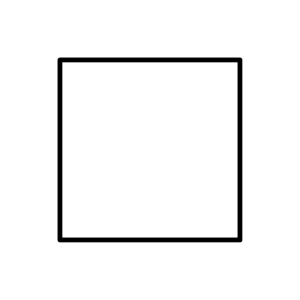

A simpler way to describe extraneous cognitive load is to take the concept of explaining a square.

There are several ways to explain what a square is.

You can do so through an aural explanation:

a rectangle having all four sides of equal length.

Or visual:

Which one is easier?

For people who possess eyesight, the second one is easier.

Thus, explaining the concept of a square using a verbal explanation is a form of extraneous cognitive load

Germane Cognitive Load – Creating Schemas

Germane cognitive load is the brain developing long-term memories, schemas, around a topic.

So, for example, if your professional domain required you to understand how to use Quickbooks, your brain builds a set of systems and processes around the use of Quickbooks and stores it in long term memory. You have to do this task perhaps every week, improving the quality and duration of your brain’s Quickbooks schema.

Germane cognitive load is the result of the constructive method of handling information, in a way that contributes to learning. Therefore, germane load refers to the work that is put into constructing a long-lasting store of knowledge or schema. This significantly accelerates the learning process.

To sum up, then, these are the three main types of cognitive load.

When cognitive load increases beyond the brain’s normal capacity, bad things happen.

The History of the Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive Load Theory was developed by the Australian cognitive psychologist John Sweller in the late 1980s.

Dr. Sweller published his research in the journal Cognitive Science in April, 1988.

Here’s how he summarized his research in the article’s abstract:

Considerable evidence indicates that domain knowledge in the form of schemas is the primary factor distinguishing experts from novices in problem‐solving skill. Evidence that conventional problem‐solving activity is not effective in schema acquisition is also accumulating. It is suggested that a major reason for the ineffectiveness of problem solving as a learning device, is that the cognitive processes required by the two activities overlap insufficiently, and that conventional problem solving in the form of means‐ends analysis requires a relatively large amount of cognitive processing capacity which is consequently unavailable for schema acquisition. A computational model and experimental evidence provide support for this contention. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

The target audience of Sweller’s audience was fellow cognitive psychologists, so let’s unpack that abstract.

Professor Sweller drew upon existing cognitive findings — types of memory, schema development, etc. — and uncovered a problem.

Students weren’t learning specific activities very well. A problem-solving task, which could be any variety of academic exercises — drew upon all kinds of schemas. Too many schemas. And schemas that the students didn’t yet possess.

So, when asked to solve a problem which required schemas, the students were limited in their ability to draw upon non-existent or multiple schemas, and just gave up.

Or they would push too hard, leading to burnout and frustration.

Cognitive Load Theory is a Big Deal

Since its publication in 1988, Sweller’s work has been cited 2,261 times and counting, suggesting its groundbreaking and influential nature in the cognitive field.

But the implications obviously spread beyond the field of cognitive psychology.

Educators, in particular, have been acutely interested in how cognitive load theory influences students’ ability to absorb and retain information.

Using the cognitive load theory, educators take measures to reduce cognitive load and increase students’ ability to learn and retain information.

Using the three types of cognitive load, educators know when and how to simplify, reduce, and maximize load types accordingly.

If you’ve dabbled in the field of education or psychology, you’ve probably encountered a discussion of cognitive load.

But for some reason, cognitive load theory has stopped there. Although its ramifications are legion, it has only been applied in a single field — education.

What I want to do next is trace out the ramifications of cognitive load theory in the arena of productivity.

What Does Cognitive Load Have to Do with Productivity?

Because cognitive load is a fundamental fact of brain functioning, its implications on productivity are enormous.

Productivity is all about the state or quality of accomplishing tasks or work.

To be maximally productive purely on a mental level, one’s cognition must be considered.

Maintaining a highly functioning cognitive state requires understanding why, how, and when cognition functions most effectively.

Issues like working memory, sensory input, memory resource depletion, and the brain’s consumption of energy are all part of this complex pursuit of productivity.

9 Productivity Lessons Based on Cognitive Load Theory

Let’s take cognitive load theory and turn it into practice.

Although most cognitive psychologists have applied the theory to education, we at KosmoTime are focused on applying the science to productivity and efficiency.

Here are 9 scientifically derived lessons that will make you more productive.

1. Perform highly demanding cognitive tasks when your brain has the capacity for the highest cognitive load.

You already know that the brain is like a muscle.

When you hit the gym on leg day, it’s pretty easy to push a lot of weight on the leg press.

But the more reps and sets, the less you’re able to push.

It’s the same thing with the brain.

When your brain hits the gym each day, i.e, right after waking up, it’s undertaking its daily cognitive tasks.

What you want to do is determine when your brain is the strongest and can thereby take on the tasks that require the most cognitive load.

What kind of tasks require a lot of cognitive load?

Any task that requires taking in a lot of sensory input and transmitting that input into short-term memory or into schemas.

Writing is one example of a high-cognitive load task. So is any task that requires taking in a lot of sensory input and then needing to transmit that information into your short- or long-term memory.

Some people are more adept with words. Some people are more adept with numbers. Brains have differing proclivities.

Know what can deplete your brain and know what is easier for your brain to do, and structure your day (and your to do list) accordingly.

2. Bundle Your Tasks Into a Few Batches

Most to do lists are useless.

When we think of something we need to do, we write it down on a to-do list.

This is the model of most task lists — ToDoIst, Wunderlist, Google Keep, Trello, Notion, etc.

They’re great at accumulating information, but they suck at actually helping us achieve completion.

In essence, our to do lists are a form of cognitive load. They pile on more information, the only benefit being that we don’t have to actively store that information in our memory.

But if you can group your tasks into just a few batches, and focus on one batch at the time, you’ll eliminate the extraneous cognitive load. In other words, it will all look simple – one batch at a time.

3. Trick Your Brain to Go into High Cognitive Load Mode

Your body funnels resources towards tasks that it recognizes as important.

For example, adrenaline will surge into the bloodstream in the event of an intense event.

Sometimes this happens autonomically, but you can also engineer your body to dump those energizing hormones into the bloodstream.

How?

You tell your body that something big is coming up. You put it into your schedule. You plan out the tasks that will be accomplished during that time, and you do it.

With KosmoTime, these are known as sprints.

Many teams and managers are familiar with sprint tasks for project management, but it’s also a smart move for personal productivity as well.

By intentionally creating and planning sprint sessions, you can accomplish up to 2-4x more than you would during a typically non-sprint period.

4. Do easy tasks after a hard task.

Once you complete a mentally demanding task, you should take a break and/or perform a mentally easy task.

This is common sense, but it goes counter to what many driven professionals are accustomed to doing.

Performing a mentally demanding task places the body in a state of hyperarousal. Our minds are already in a high-RPM state and we feel like the momentum and adrenalin can carry us into another challenging task.

But cognitive load theory says otherwise.

According to research by John Sweller and other cognitive psychologists, you shouldn’t do a hard task after doing a hard task.

They called it the “depletion effect” and wrote about it in detail in the journal, Educational Psychology Review, under the title “Extending Cognitive Load Theory to Incorporate Working Memory Resource Depletion: Evidence from the Spacing Effect.”

This is one of the most direct practical outcomes of the cognitive load theory, and introduces a child concept known as the spacing effect.

The spacing effect states that your brain is much more capable of learning and accomplishing tasks by taking a break between highly demanding tasks.

5. Plan your day with extreme detail.

The less you have to think about what you’re doing, the more you can do.

Before your day begins, create an exacting list of what you intend to achieve. When you create your “list,” treat it more as an operating manual than a mere list.

- Include any links to pages or files that you need to access for that task

- Add contextual details about the task to jog your memory or to enhance your ability to achieve the task

- Define exactly when and for how long the task will take

This kind of planning is more arduous than jotting things down on a to do list, but it’s enormously more rewarding and contributes to maximal productivity.

Why?

By planning the details of your day in advance, you are removing the layers of cognitive load that are required to start a task.

It sounds cliche, but the hardest part of starting is starting.

By creating a to do list that makes starting easy, you’ll easily ramp up to your tasks and accomplish them with greater ease.

Will your day flow in keeping with your detailed plan?

Probably not.

But will you have a greater sense of control than you were to have if you neglected to plan in detail?

Definitely yes.

5. The More Granular the Task in Your To Do List, the More Effectively You Can Achieve It. Then Batch It

It’s probably obvious that gargantuan tasks in a to-do list are basically useless.

Let’s look at an example.

Task: Prepare Seattle’s Keynote Speech

What are you going to do with that?

Nothing. It’s too big.

Cognitive load theory states that a problem space is that void between your current situation and a desired outcome.

If the gap is too big, your mind tries to fill it by drawing on a disparate array of schemas, which is a cognitive overload.

You need to reduce the problem space into something that’s nice and tidy.

Task: Determine the topic for Seattle’s keynote speech

Much better, right? You’ve given your brain far less schemas upon which to draw, and more specificity as to what you want the outcome to be.

The distance between present state and goal is shortened, and the task becomes far more attainable.

Of course you will then end up with a larger list of tasks. This is where batching comes in: Group your related tasks in a Sprint in KosmoTime, and you get the best of both worlds!

6. Plan your day with accessible action items.

What do I mean by “accessible action item?”

An accessible action item is one for which the “accessories” are readily available.

For a task like “go fishing at Lake Keowee,” your accessories would be bait, tackle, fishing poles, etc.

Let’s put this in the context of your office job.

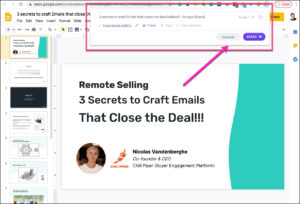

For example, let’s say one of your tasks is to “review Nicolas’s presentation.”

This is a real task on my list right now.

Now, if your to do list is like most people’s, that line item is going to sit there.

You’re going to stare at it, blink a couple times, and skip it.

Why? Because Nicolas’s training video is in some random Drive file. Or maybe the Slack thread? Or did he send it to you?

Where the heck is it?!

Suddenly, your working memory is spreading itself in 17 different directions asking way too many questions about this simple task.

You’ve hit a high degree of cognitive load, effectively shutting down optimal mental performance.

The limits of your cognitive load have been surpassed. Instead of taking on the onerous task of hunting down that video, you’re going to find a different task to accomplish that won’t obliterate the limits of your cognitive load.

This, in turn, creates a new problem called task switching, a whole different productivity-killing animal.

Now, let’s rewind to the beginning of that task. What if you had, instead, bookmarked Nicolas’s training video when he sent it to you?

It looks like this.

Nicolas emailed the presentation to me two days ago. When he did, I clicked on my productivity plugin, and added the task.

Two clicks, boom.

Instantly, that task was added to my to do list.

Now, when it’s time for me to do that task, I click on it — the link to the Drive presentation is embedded into the task itself — and start working on the task.

Better yet, this productivity plugin has a distraction blocking feature.

Which leads me to yet another implication of cognitive load theory on productivity.

7. Did I Say It Before? Batch.

Batching is one of the most underestimated productivity tools, popularized by Tim Ferriss in the Four Hour Workweek and praised by many productivity gurus.

Batching is simple. You focus on accomplishing a group of similar tasks during a certain period of time.

Examples?

- You focus on emails and only emails from 3-4 pm on Monday.

- You review and pay invoices and only invoices during 10-11:30 on Wednesday morning.

- You set aside time to write a Medium article from 8-11 am Thursday.

The cognitive load theory explains why batching is so effective. By minimizing disparate aspects of cognitive input, your brain settles into a productive groove, warming up the neural pathways responsible for helping you achieve meaningful work.

The opposite of batching is task switching, a productivity killer that we mistakenly refer to as “multitasking”

Task switching refers to the practice of working on one task and then transitioning to another task. In doing so, you are subjecting your brain to a higher cognitive load and losing time due to the switching process.

The way to start batching is simple.

Gather a group of similar tasks that you need to accomplish, and focus on just those tasks for a certain period of time.

KosmoTime makes it easy to do this.

Each of your tasks can be tagged or placed into specific projects. So when it’s time to focus on, say, marketing activities, you select your marketing tasks and queue them up for the day.

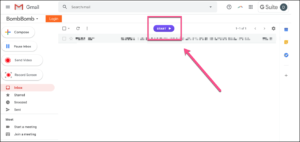

8. Place your email time into its own box.

Email has the potential to become a devouring monster.

That’s why it deserves a section of its own.

Email is one of the most cognitively demanding tasks, not just because of the quantity of emails that most of us receive, but also because it draws heavily on our mental resources.

There’s no silver bullet for effortless email management, but there are simple ways to achieve flow and become more productive with your email.

The first way — isolate email as its own task and remove all distractions from completing that task.

KosmoTime places a small “start” button at the top of your inbox.

When you click on “start,” you can block distractions and focus exclusively on email.

What happens next?

- Your browser tabs close down. (Don’t worry; they’re easy to open with one click once you end your email session.)

- Your Slack session goes into busy mode.

- You start slaying like a freaking machine.

Cognitive Load Theory – More Productivity, More Achievement

Cognitive load theory has the potential to change how you approach your workday and how much you are able to achieve.

The key to unlocking many of these implications is to use the app KosmoTime

KosmoTime is an app that was developed based on the findings of science — behavioral psychology, motivation theory, and of course, cognitive load theory.

By using KosmoTime, you’re not simply creating a list of tasks that you hope to get to someday.

You’re using a tool that allows you to truly achieve massive amounts of meaningful work.

Start using KosmoTime now.